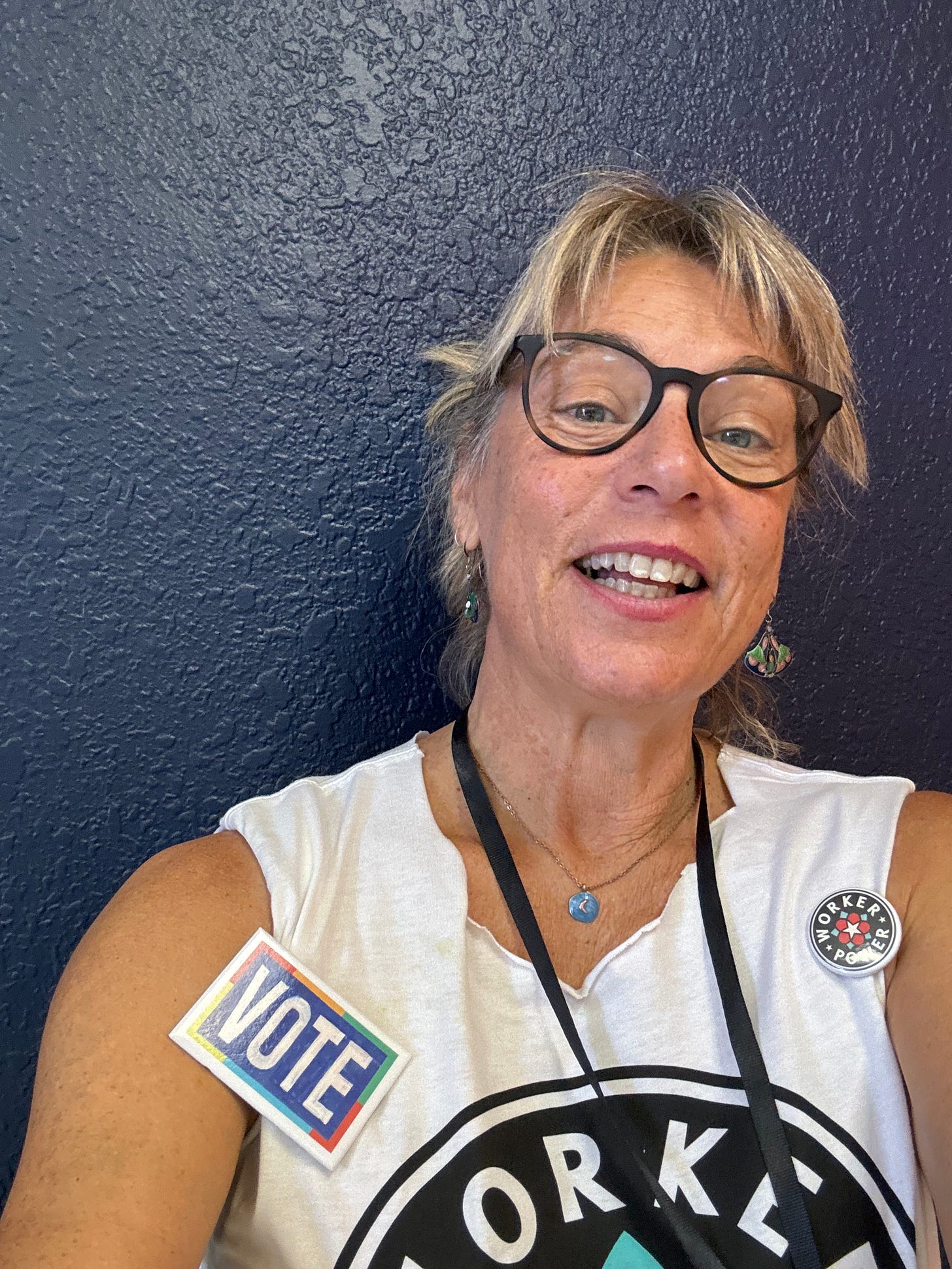

Knock-Knock-Knocking To Save Democracy

What It's Like Out There

Standing in front of a closed door, preparing to knock, I pause and take a second to visualize the person on the other side being glad to see me. It’s easy, when knocking on doors during an election in a swing state, to start anticipating the hostility that might come your way. But I find that the hostility is less likely to come if I don’t gird myself …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to A Sigh of Relief: Talking About Justice & Accountability to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.